Alex Daly (later known as Alex Ritchie, after his biological father) was a bright pupil at DHS, with a gift for science and mathematics. After school he took a B.Sc degree at the University of Natal and then emigrated from South Africa to the UK, where he did postgraduate research at Cambridge University.

Alex settled on the east coast of England and set up his own engineering shop. He proved to be an exceptionally skilled engineer with a gift for solvng difficult or unusual problems and soon gained great renown for his work. In 1997 he was approached to design a capsule and burners for Sir Richard Branson's round-the-world hot air balloon. Alex worked closely with Branson in 1997 and 1998, and travelled with him to Morocco for test flights. While awaiting delivery of a new balloon, the team practiced free fall parachuting. On one drop Alex's parachute opened too late and he was badly injured. He was flown back to hospital in the UK but died there three months later, after several operations. He left a wife, Jill, and two sons.

Here is a photo of Alex on a school art department trip to the OFS in 1961 (photo by classmate David With).

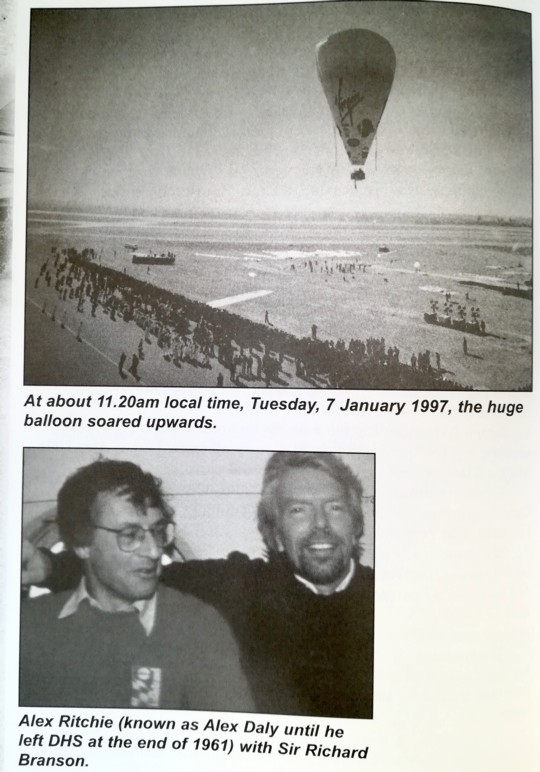

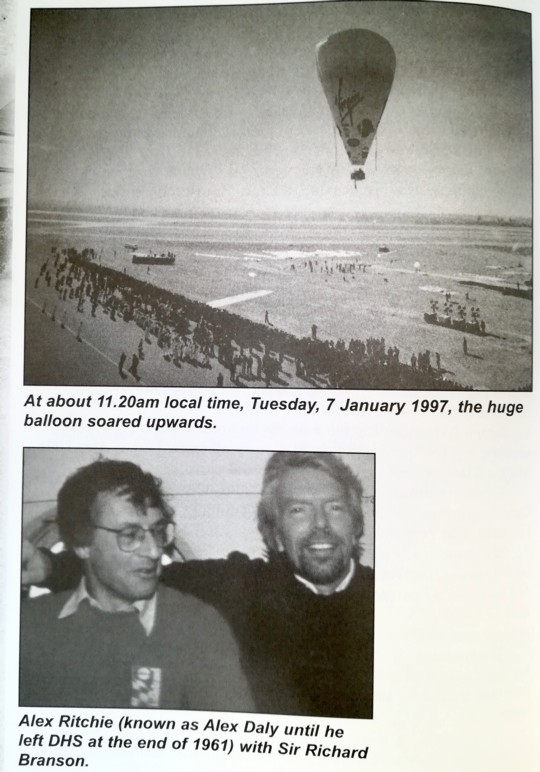

ALEX RITCHIE, who achieved international fame with his epic rescue of Richard Branson and his Virgin Global Challenger balloon at the very start of their attempt to fly around the world in January 1997, was an engineer who contributed as much as anyone to the rebirth of interest in long distance ballooning.

His trademarks were inventiveness and versatility, a combination that led some to dub him "a cross between Heath Robinson and the 21st century". He was an allrounder who had mastered technologies ranging from turbojets to gas diesel engines. He was involved not only with ballooning, but other "retail" cutting-edge ventures including the successful attack by Richard Noble's Thrust SSC on the world land speed record.

On a personal level as well, Ritchie fitted the legend of gifted Scots engineers who helped build industrial Britain. He was quiet and understated, yet a splendid storyteller. Above all he was cool under pressure - a quality never more in evidence than during the drama in the early hours of 6 January 1997.

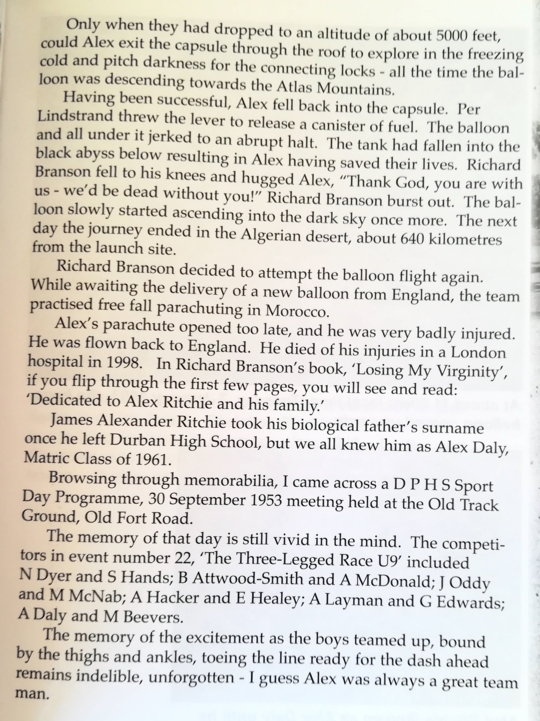

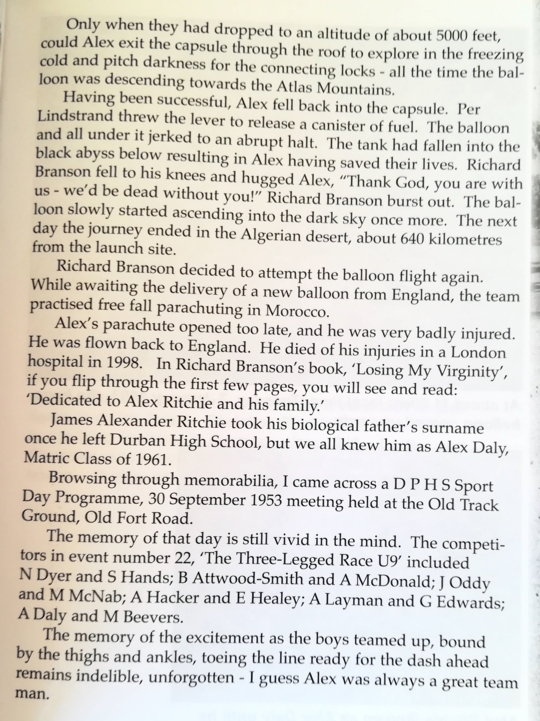

It occurred less than 24 hours after Virgin Global Challenger, carrying Branson and his two co-pilots Ritchie and Per Lindstrand, had taken off from Morocco and set off east across the Sahara desert. The balloon had crossed into Algeria at an altitude of 30,000 feet when it began losing height precipitously, hurtling towards the ground at 40 feet per second.

Instantly grasping the urgency of the moment, Ritchie climbed on to the roof of the capsule, wearing a parachute and strapped to Challenger's fuselage. He jettisoned a fuel tank and other equipment, slowing the balloon's descent and enabling it to make an orderly landing. Branson later described the experience as "terrifying". Without his co- pilot, he gratefully acknowledged, "we would have gone into the ground. He saved our lives and is the hero of the hour. He showed unbelievable bravery."

Ritchie himself however was unflappable. Algeria was and remains an exceedingly dangerous country. Yet he was less concerned with the arrival of the helicopter gunship sent by the government which arrived to carry them back to civilisation, than with getting up-to-date on the latest football results.

Almost exactly a year later, also in Morocco, came the sky-diving accident which would ultimately claim his life. Training for another balloon bid, he fell some 13,000 feet onto a concrete car park when his parachute failed to open properly. He was taken back to Britain with a broken leg, pelvis and arm. There he underwent nine operations but developed a form of blood poisoning which proved fatal.

Alex Ritchie was a fully qualified and highly experienced gas balloon pilot and hot air balloon pilot, who designed and built the burners and engines for all three Virgin Global Challenger ventures. After taking a science degree at the University of Natal, and conducting machine tool research at Cambridge University, he spent three years as a project engineer for British Leyland. He later had spells at Noel Penny Turbines and Caterpillar Tractor, working on automotive gas turbines. At the time of his death he headed the family business J. Alex Ritchie, where he worked with his son.

His connections with Virgin Challenger however will live on. Richard Branson plans to dedicate next winter's round-the-world attempt to him. Even more pertinently, it will use a capsule designed and built by Alex Ritchie.

James Alexander Ritchie, engineer: born Glasgow 19 January 1945; married 1970 Jill Neave (two sons); died London 12 April 1998.

New York Times obituary:

Alex Ritchie, 52, Balloonist, Dies After Sky-Diving Mishap

By ERIC PACE

Published: April 14, 1998

Alex Ritchie, a British balloonist who clambered atop an airborne balloon's gondola last year to jettison fuel tanks, halting a crash-dive, died on Sunday at Middlesex Hospital in London. He was 52 and had been undergoing treatment at the hospital since January.

Alex Ritchie, a British balloonist who clambered atop an airborne balloon's gondola last year to jettison fuel tanks, halting a crash-dive, died on Sunday at Middlesex Hospital in London. He was 52 and had been undergoing treatment at the hospital since January.

The cause of death was injuries he sustained in January in an accident while sky diving, according to The Associated Press. It reported that the office of Richard Branson, a wealthy British entrepreneur and balloonist, said Mr. Ritchie had come down with blood poisoning after surgery to repair one of his hips.

Duncan Ritchie, 20, a son of Mr. Ritchie, said, ''He was a fighter and carried on fighting until the end.''

In the ballooning incident, which occurred in January 1997, Alex Ritchie, a Scottish-born mechanical engineer, was part of a crew trying to circle the globe. Twelve months later, he was preparing for another try at ballooning around the globe when the sky-diving mishap took place.

He was honing his skill at sky-diving in west central Morocco near the Atlas Mountains when his parachute failed to open, and he tumbled from 13,000 feet onto an airfield, breaking his pelvis and his arms, gravely injuring one leg and suffering internal bleeding.

Mr. Ritchie said he tried throughout the fall to get his chute to open. It opened partly near the end of his descent, saving his life. An aerial ambulance flew him to Britain, where underwent a series of operations.

Mr. Ritchie; Mr. Branson, the chairman of Virgin Atlantic Airways among other companies; and Per Lindstrand, the president of Lindstrand Balloons of Britain, were crewmates last year in their failed attempt to become the first to circumnavigate the globe by balloon. Mr. Branson was the captain and main sponsor of the balloon, the Virgin Global Challenger.

Mr. Ritchie, like Mr. Branson, was drawn by the challenge of trying to fly a balloon around the world. Not long after the unsuccessful flight, Mr. Branson said: ''As I was sitting in the capsule while our balloon was plunging uncontrolled toward the earth, the thought crossed my mind that maybe a round-the-world flight really is impossible. But we stopped our descent in time to avoid a crash, and I've come back to my conviction that circumnavigation is possible. I'd put money on someone doing it 24 months from today.''

The Virgin Global Challenger took off from Marrakesh, Morocco. After the near-crash, Mr. Lindstrand said that before the takeoff someone had neglected to remove the safety catches that held fast a half-dozen sizable fuel tanks to the exterior of the balloon's crew capsule.

He ascribed the oversight to too much work and too little sleep by the ground crew during preparations.

''After we were up,'' Mr. Lindstrand said in an interview, ''we got an emergency message from the ground that the safety catches had been accidentally left on. That meant we couldn't release any of the tanks from inside the pressurized capsule if we needed to jettison them.''

It did become essential to release the catches, and to do so, someone had to crawl out from the crew capsule after the balloon descended to an altitude at which the gondola's hatch could be opened. On the evening after takeoff, the balloon got down to 10,000 feet. But then a vicious air current forced the balloon to bobble. The craft began a crash-dive toward the earth.

Trying to get the balloon to regain buoyancy, the crew threw all loose objects out of the gondola. And then, in a last-ditch measure, Mr. Ritchie clambered atop the capsule, perched there and unfastened the fuel containers, which came loose in the nick of time to halt its deadly descent.

Afterward, the crew decided to abort the mission and to land, because losses in supplies, helium and fuel had rendered their flight impossible. The balloon landed in the Sahara after less than a day in the air, and Mr. Branson said: ''We owe a debt of gratitude to Alex. He saved our lives.''

In addition to his son Duncan, Mr. Ritchie is survived by his wife, Jill, and by another son, Alasdair.

Addition from Jeremy Oddy (Class of 1962) , December 2017.

Jeremy Oddy, who knew Alex well and later became Archivist for the school, has submitted the extract below from his book about DHS, Where the Baobab Grows (2008).

.jpg)

![]() Alex Ritchie, a British balloonist who clambered atop an airborne balloon's gondola last year to jettison fuel tanks, halting a crash-dive, died on Sunday at Middlesex Hospital in London. He was 52 and had been undergoing treatment at the hospital since January.

Alex Ritchie, a British balloonist who clambered atop an airborne balloon's gondola last year to jettison fuel tanks, halting a crash-dive, died on Sunday at Middlesex Hospital in London. He was 52 and had been undergoing treatment at the hospital since January.

.jpg)

Richard Dold

I remember Alex as a smallish guy with a really impish sense of humour. One of his wheezes which comes to mind was when he put a sign on the classroom notice-board.

It consisted of a piece of paper which was folded in half.

The visibly displayed half read, "Lift in case of fire!";

then when one lifted it up, it revealed the words, "Not now silly! Only in case of Fire!"

It's the sort of harmless schoolboy humour which has gone down well whenever I've used it with my classes during my years of teaching.

Roger Sheppard (Class Of 1962)

I believe this Alex Daly attended DPHS. If this is the same fellow, I recall that his family gave him a lead model replica of the coronation coach, in which QE II was driven on her way to and from her coronation. He brought this to school, complete with lead horses and handlers, and we were enthralled. The model certanly was presentable in its accuracy, as we had studied pictures in the press of this display of grandeur at the time.

It aslo represented immense local wealth, to us in post-war Durban of the '50s.

Perhaps someone can recall this and add / subtract from this ageing memory's account.

Roger Sheppard

Leslie Closenberg

Alex was in my class through most of DPHS and I recall his "father" in Durban was the owner of a cool drink factory. Their product was all over Durban called, of course, Daley's.

I also have a vague memory of his being extremely interested in model trains so that his eventually becoming an engineer is understandable.

Les Closenberg

Frank Bullock

If I remember correctly, Alex Daly, went to Chelmsford School (at that time on the corner of Berea Road and Musgrave Road). That was before he went to DPHS, which only started at Std 2. I visited him at home at that time (caught the bus with him from Chelmsford School, so we were little kids.) He had at that young age model steam engines that worked, and indeed model trains. He obtained a B.SC. engineering degree from Natal University - I think he got bored at some time having to study tables of properties of steam. I remember him complaining once about that.

Richard Bell

Alex Daly was in V AMB & VI AMB with me in 1960 & 1961. He was a quiet little chap who classmates hardly used to notice. One would say "hello, Alex" to him & that would be that. I can't remember ever engaging him in conversation.

Who would ever have thought that Alex would turn out to be such a hero ?