Abstract

Within his social millieu, Aubrey Langley was lauded as one South Africa’s finest headmasters. He served as headmaster of Durban High School (DHS) from 1910 to 1939. He was feared and loved with a reputation for fierce discipline, devotion to the game of rugby and a love of classical education. In this paper we explore his place in the history of colonial Natal and explain how a man renowned for thrashing his pupils had the wholehearted support of parents and the Natal settler community more broadly. In the first quarter of the twentieth century, Natal was witness to three major armed conflicts, the Second South African war, the Bhambatha Rebellion and the First World War. In the wake of the earlier catastrophic defeat at Isandhlwana in 1879 the settler population needed no persuasion that war-readiness should be a key part in the education of its boys. We argue that the commitment to muscular Christianity, team sport and corporal punishment rested on settler insecurity and a preoccupation with the precariousness of white rule. In this climate, Aubrey Langley was considered a potential saviour and his excesses readily excused and his triumphs lionised.

Imagine this scenario: a moustachioed Edwardian headmaster calls five or six boys guilty of smoking to the lectern during a school assembly and publicly canes them. He then asks the rest of the school to step forward if they are guilty of the same offence. Four hundred boys, about 70% of the school, confess. After the headmaster flogs all the smokers, he decides to cane the remaining 30% for ‘good measure’.[1]

Although this scene sounds like it sprang from the pages of one of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels, it is not fiction. The headmaster in question was a man by the name of Aubrey Samuel Langley and the incident occurred at Durban High School (DHS) sometime in 1917. Instead of being arrested or fired for these actions, Langley was considered, by his superiors in the Colonial Education Department, parents and historians, [2 ] as one of Natal’s most successful headmasters. [ 3]This opinion was shared by the vast majority of the 13,000–18,000 men who Langley taught at Maritzburg College (MC) and DHS as these young men revelled in the fact that they had survived and gained the respect of this tough rugby player, hunter, tireless proponent of tedious Latin grammar and unflinching disciplinarian. Langley’s popularity was such that 1000 vehicles made up the motorcade at his funeral in 1939. [4]

Whilst his professional and personal popularity may seem bizarre to modern parents and pedagogists, Langley’s educational philosophy was admired by Natal’s white English-speaking middle class whose fears and social aspirations were catered for by his brand of masculinity and the methods he employed to disseminate this version of masculinity amongst his students. In this article we present a slice of Langley’s life as a window into the workings of the schooling of upper class white boys in early twentieth-century Natal. Langley’s story, whilst not extraordinary in the sense that many of his beliefs and practices were shared by his predecessors and contemporaries, is worthy of study. The sheer weight of his personality, a personality Peter Randall said still haunted the hallways of his school 40 years after his death, [5] serves to exemplify the practices of the era and reasoning behind them.

In our analysis we focus on the means by which English settler masculinity was moulded in schools and how this was framed by their anxiety about war and the threat posed by their Afrikaner and Zulu neighbours. This anxiety justified an approach to schooling which stressed discipline and a curriculum and pedagogy that connected Natal’s white settlers to the United Kingdom from where many had come and to which many still retained a strong attachment. [6]

We describe three domains where Langley’s approach to schooling was most evident: team sports, corporal punishment and classical education. We set this discussion against the biography of Langley himself and argue that the times made it possible for Langley to rise to the pinnacle of the teaching profession, to gain support for his methods and to be idolised.

Segregated schooling in twentieth-century Natal, white boys’ schools and the role of the headmaster [7]

Aubrey Langley presided over one of the oldest secondary schools in colonial Natal. DHS had been founded in 1866. The oldest secondary school, MC, had been founded in 1863. He had taught there too. These were schools founded in terms of two laws passed in 1861, the Pietermaritzburg Collegiate Institution Law 18 and the Durban Collegiate Institution Law 19. These demonstrated the colonial government's intent on extending schooling for its white male population. With Responsible Government for Natal achieved in 1893, a Ministry of Education for the first time was created and increased funding made available for schooling. At this stage, there were no government-funded secondary schools for girls. Support for girls’ schooling was provided via grants-in-aid to private schools, set up by individuals and churches to service the needs of settlers. [8] The impulse to education was however not confined to the settler population. Mission-based education for African boys and girls was also being pioneered. Amongst the most prominent of these initiatives was Adams College (established 1865) and the Inanda Seminary (1869), both established by the American Board. Schools for Africans received virtually no financial support from government but there was nevertheless spectacular growth. In 1915 there were 302 mission schools with 21, 700 pupils. [9] Amongst Indians, Christian, Hindu and Muslim, schooling emerged via a variety of initiatives in the late nineteenth century. These included missionary institutions and those created by civic associations, for example the Durban Indian Educational Institute (1911) which extended education provision beyond Standard 7. In 1909, there were only five government schools and 31 aided schools, with an enrolment of 3387 pupils. [10]

Segregated as these schools were and in large measure each serving separate and distinct communities, they developed along distinct paths. As both Vahed and Waetjen and Healy-Clancy have shown, the schools serving the colony’s black populations, despite receiving scant support from government and often hindered in their purpose, provided important spaces for the development of a cadre of leadership and community, both of which contributed to a longer-run assertion of identity and rights. [11]

Insofar as DHS was concerned, the school benefitted from generous government support. Even its location, perched on Durban’s Berea and amongst the houses of the middle classes who inhabited the suburb of Musgrave, spoke of its privileged location. Schools like DHS do not automatically fulfil the mandate of the government; policies envisioned by officials require implementation. As the oldest secondary school in Durban, ministering to the next generation of settler leaders, Natal’s Educational Department sought a DHS headmaster who would turn curriculum and pedagogy into lived school reality and produce educated, raced, gendered and classed, products. Whilst Langley did not possess a degree from an Irish or British University, a formal requirement of headmasters of government (and private) schools in nineteenth-century Natal, [12] he was appointed to head DHS in December 1910 because his beliefs, idiosyncrasies and charisma satisfied the cravings of Education Department and parent body.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the headmaster of secondary schools was an awesome figure, commanding respect, instilling fear in his charges and enjoying government support as he did so. School histories routinely periodise by discussing the period of a headmaster’s reign. Its success or failure is often considered as an effect of the headmaster’s strength and weaknesses. At the turn of the twentieth century, in the United States, the ‘creation of the principal’s (headmaster’s) office revolutionized the internal organization of the school’. The principal was given authority over other teachers and the pupils ‘realigning the source of authority from the classroom to the principal’s office’.[13] This is an important observation and only needs one qualification – that in colonial Natal the headmaster had formal power and authority and, with the steady increase in the size of secondary schools, such powers became more apparent. But the headmasters of Natal were not merely managers, hidden in their offices. They were energetic and highly visible, and none more so than Langley. He exhibited what researchers have subsequently come to identify as important areas of performance of the principal: ‘the importance of modeling through one’s own actions the values, beliefs, and normative behaviors on which cultures are founded.’ [14]

Given the visibility and power of principals in these settings, the personality and actions of the principal become important. In a recent review of Jeff Guy’s work on Theophilus Shepstone, Norman Etherington noted: ‘Not for a very long time have I read a work of historical scholarship so concerned with moral character […] Is it not time to revisit the question of character?’ [15] Drawing on Etherington’s observation, an investigation into the impact of the character of headmasters like Langley will provide valuable insight into the formation of the masculine identities of the young men who attended these schools.

Schooling masculinity

Boys schools are renowned for being masculinity factories. [16] As social organisations, schools mould boys in a particular way. The influence of the very old, elite, private boys’ schools of England, the public schools, on masculinity and the class structure of the United Kingdom is amply illustrated and analysed across the centuries. [17] The model of muscular Christianity became a feature of these schools in the nineteenth century. [18] The public school model of elite schooling for boys featuring corporal punishment, sport participation, classical education and forms of dress and behaviour associated with the British landed gentry was imported into South Africa in the late nineteenth century. [19 ] Schools set up by colonial government and the church adopted the educational approach of British public schools. These included the private Christian church denomination schools – St Andrews (Grahamstown), Bishops Diocesan College (Cape Town), St Johns (Johannesburg), Hilton College (Natal, non-denomination) and Michaelhouse (Natal) – and government schools, MC and DHS (Natal). All of these schools featured headmasters who shared an academic, discipline and extra-curricular philosophy similar to that of Langley’s. At Bishops, for example, George Ogilvie (1861–1885) was described as ‘severe when severity seemed necessary and when roused he was awesome. He had a stern face, a resounding voice and a strong right arm.’ [20] At St Andrews, Headmaster Percy Kettlewell (1909–1933) was described as ‘tall as a stone pine and just as tough, his dashing black straw boater tipped at an angle over his eyes’. [21] His recourse to corporal punishment was ‘swift and perfunctory’ and for him ‘duty was sacrosanct’.[22]

Langley was not so much an exception but rather an example of what was considered to be a model headmaster. He was somebody who believed in the importance of games, stern discipline and classical education and whose views had been shaped by having grown up in colonial Natal and having absorbed the views of race and class that were developed towards the end of the nineteenth century. Langley accepted, with only a slight disagreement with regards to the future of the classics, the model of schooling propagated by the British colonial and, later, Union officials who were attempting to establish a wider British control through schooling. [23] Considering the violent history of colonial Natal, these officials were especially keen on implanting the public school system as they noted its reputation for producing resilient young men. When Langley was acting headmaster of MC in 1908, Natal’s Governor Sir Matthew Nathan gave a prize-giving speech entitled ‘Duty of Young Natal’ in which he highlighted the faith colonial administrators had in character building aspects of the public school model and its value to the British Empire:

it is evident the College fulfils satisfactorily one of its purposes, that is, the training of boys’ minds. I have no reason to doubt that it carries out its other great function, that of forming their character. Of the two purposes I am inclined to think that in the conditions of this country the second is possibly of a greater importance. The conditions are such that every boy has to learn to be a ruler […] hence it is primarily necessary that they should acquire in this college those qualities of fearlessness, patience, broad sympathy, and quiet unassuming strength, which have enabled boys trained in the public schools in England to rule hundreds of millions of natives in Asia and Africa, and to maintain Pax Britannica among them …[ 24]

Such sentiment was echoed, though with more anxiety about the precarious condition of colonial dominance in Natal, by Ernest ‘Pixie’ Barns in his headmaster’s address at the MC Speech Day in 1914: ‘it must also be remembered that in the peculiar conditions of life in this country, where the white man is outnumbered 10 to 1, an efficient body of young men well-trained and well equipped is a permanent necessity.’ [25]Aubrey Langley

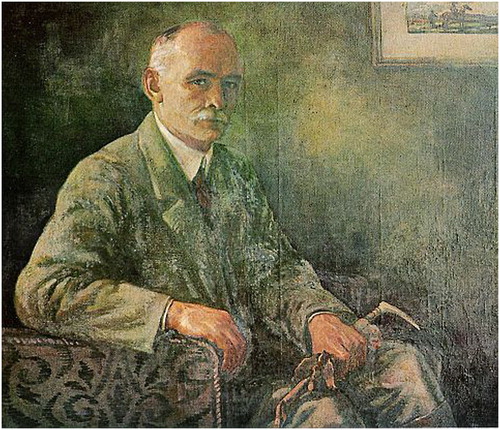

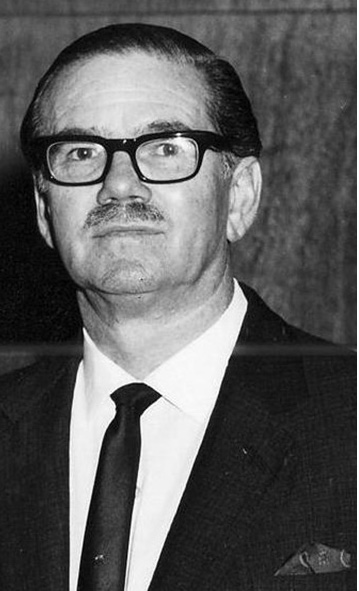

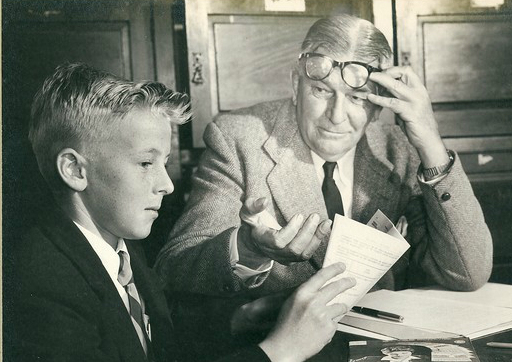

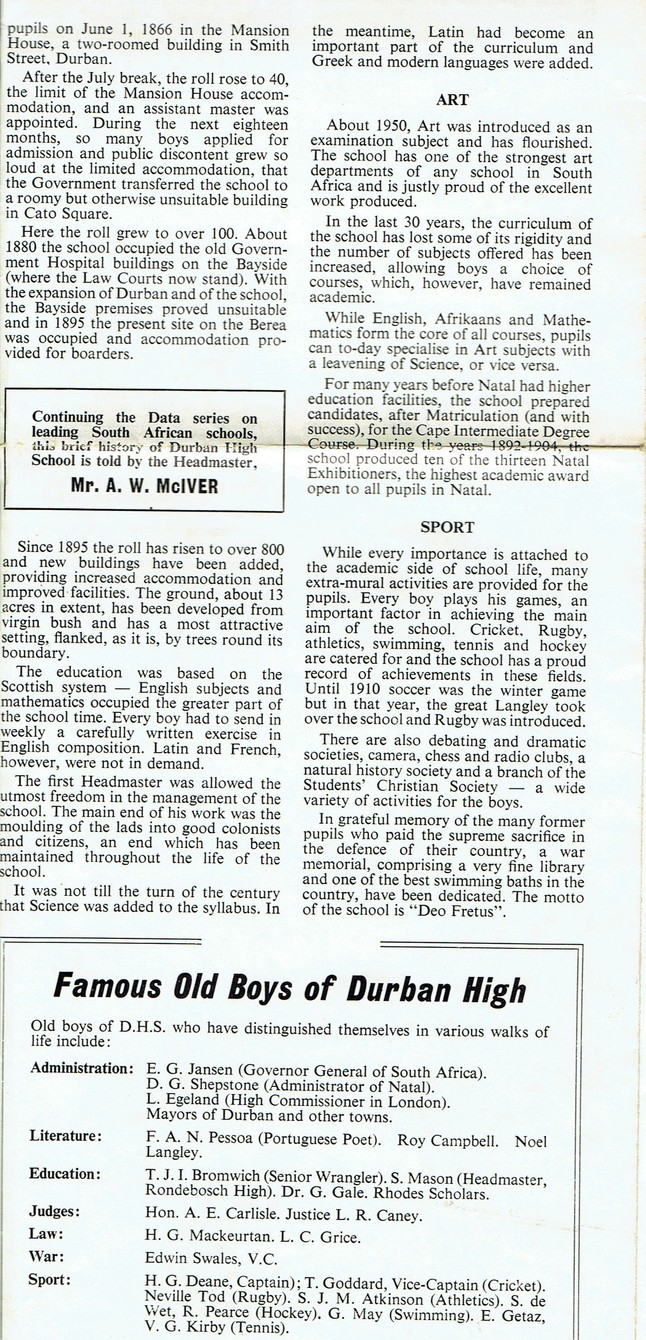

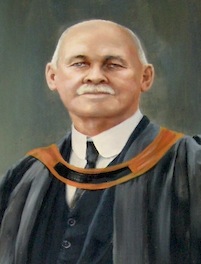

Measuring six feet with a 38-inch chest, [26] icy blue eyes and a reputation for violence, Langley embodied the Victorian physical ideal. His thick and flowing moustache epitomised the martial masculinity he wished to portray and was admired by both his students and his Zulu employees, whose fascination with facial hair [27] led them to honour him with the manly praise name ‘Madevu’ (moustache) (see Figure)

Figure Aubrey Langley at Maritzburg College in 1900. © Maritzburg College Archives. Permission to reproduce photograph granted by Matthew Marwick/Maritzburg College Archive.

Aubrey Samuel Langley, the second son of the Rev. James and Emma Langley, was born in Pietermaritzburg on 25 June 1871. In 1872, 12 years after Rev. Langley arrived in Natal, [28] his parents moved 40 km North to the rural hamlet of York to set up a missionary station and school. It was at York that Langley first came to realise just how precarious was British dominion over Natal. In his memoirs, written six decades later, he describes York (50 km from the Zululand border) in the 1870s as ‘living on the edge of a volcano’ with ‘general talk of the warlike character of the Pondos, of the unbeaten Basutos, of the Swazis and other tribes … ’ [29] When Langley was eight years old York descended into panic after the white settlers and their African servants received news of the British defeat at Isandlwana. In his memoirs, Langley notes the hysteria and fear that spread through the white population of Natal after the defeat. Fearing that the rampant Zulu army would march on white settlements in Natal, York’s townsfolk began preparing for, what they assumed would be, the inevitable Zulu attack. Langley proudly notes that he helped barricade buildings and overheard one of the residents explain how he would use his axe on any of the Zulus who managed to break into his position. This episode left an indelible impact on Langley who stated that his father’s heroic, but illegal, requisition of ammunition during the invasion scare was one of only two positive memories he retained of his father. [30] The episode also showed Langley that the British control of Natal was only as strong as that of physical and mental fortitude of its colonists.

Shortly after conclusion of the Zulu War in 1879 Langley’s father sent him to receive a ‘decent Methodist education’ at Kingswood School in Bath, a minor public school for the sons of Methodist ministers. It was at Kingswood that Langley was taught to see manliness, and its associated physical and mental strength as emanating from the public school system and its obsession with team sport, corporal punishment and the classics.[31] After scraping through Kingswood’s final examinations, Langley continued his association with the system by taking up a few mastering and teaching roles at minor English public schools. Langley returned to South Africa in 1896 and in 1897, inspired by his public school experiences, took up a position as Senior Resident Master at MC. It was at MC that Langley was reminded of the fragility of British Natal.

In November 1899 at the outset of the South African War, just over two years after Langley took up his position, MC was taken over by the British Army and converted into a military hospital. [32] During MC’s military occupation Langley conversed with many of the British soldiers, some of them former pupils, recovering from wounds and illness and learnt of the early British defeats at Ladysmith, Colenso, and Spioenkop. Although these conversations must have alarmed him, they also convinced him that the public school system was the answer to many of the threats posed to the British Empire. Less than seven years later he served as a subaltern in the Natal Carbineers during the 1906 Bhambatha Rebellion. Despite being reminded of the insecure position of white rule in Natal when he lost a man under his command, [33] his observations during the campaign confirmed his belief that elite boys schools of the empire needed to continue and extend their policy of promoting muscular Christianity.

Muscular Christianity

Muscular Christianity is a Victorian belief that sport built the morality, physical fitness, and ‘manly’ character of young men. [34] Along with the religious motivations, which warned that the Anglican Church was becoming effeminate, it was Victorians’ obsession with health in their industrialising society that produced this belief. British industrialism led to an increase in inactive and industrial occupations, and increased frequency of cardiovascular diseases. Academics and medical professionals alike expressed concern. Proponents of muscular Christianity suppressed this concern by highlighting the fact that the ills of industrialism could be overcome by another of its by-products, an increase in leisure time and participation in sport. [35]

A renewed thirst for muscular Christianity emerged throughout the British Empire after its costly victory over the Boer republics in the South African War. Many Britons began to question the health and physicality of their menfolk and in 1903 the Director General of the Army Medical Services established the Committee on Physical Deterioration to investigate. [36] The Committee’s 1904 report confirmed British fears explaining that dreadful working and living conditions [37] led to a nearly 60% rejection of working-class applicants to the military. [38] Whilst the committee’s findings focused on decline of physicality of the British working-class male, a series of colonial rugby tours to the British Isles suggested that the upper classes also lacked the muscle needed to protect their empire.

The ‘Springbok’ tours of 1906–1907 and 1912–1913, ‘All Black’ tour of 1905–1906, and the Australian tour of 1908–1909 humiliated the national rugby unions of Britain. Out of the 130 games played, the touring colonials won 117. The game of rugby was seen as ‘the best trial of the relative vigour and virility of any two or more opposing countries’ [39] at the time and the disastrous results of these four tours added to the negative press surrounding the state of British manliness. As rugby was considered upper class, these tours suggested that the decline highlighted by the Committee on Physical Deterioration was not isolated to the working poor.

In the wake of the report and rugby tours, numerous British commentators began calling for muscular Christianity to halt the decline in British masculinity. Back in Natal, these idea informed settler thinking and Aubrey Langley noted an ‘evident demoralisation’ in the white community of his locality. The insecurity Langley felt as a result of this deterioration was compounded by the fact that Natal’s settlers were ‘surrounded by savagery’. [40] One of Langley’s solutions to this challenge was to emphasise the importance of team sport.

Team sport

Langley was a talented sportsman with a love of the outdoors. He was an avid fly fisherman, [41] cricketer, [42] rugby player, and rugby administrator who entrenched the game at both MC and DHS, helped establish the Old Collegians Rugby Club, [43] and chaired the Natal Rugby Union in 1900 and 1901. [44] Langley lauded the achievements of his schools’ sportsmen and consistently promoted them to positions of schoolboy authority. These young men revelled in Langley’s applause and served as devoted guardians of his traditions. Thousands mustered at his funeral in 1939 and a select few served as pallbearers. [45]

Through school sport, Langley aimed to promote amongst his pupils a masculinity that was physically robust, quick thinking and selfless. Langley’s obsession with sport and its promotion at a schoolboy level are also testament to his mission to promote the idea that both he and his students were upper-class, colonial companions of the public school elite of the British mainland.

The first benefit Langley saw in team sports is outlined in his 1908 address on the ‘The Function of Athleticism’ in Education which states that athleticism provided ill-disciplined boys with an outlet for their ‘savagery’, and served to improve the academic capabilities of students who transfer the self-discipline and competitiveness developed on the field into the classroom. [46] Langley also argued in this address that sport would curb the apathy and individualism that was weakening the British Empire and promote an ‘instinct of preservation’. He believed that there was ‘a defiant reluctance to accept any attempted organisation which necessitates control of communities by the individual’ and ‘a false idea of the Britisher’s rights’. These could be eliminated through team work and a disregard for one’s personal gain. Again and again he reminded his students of this by criticising selfish players, [47] encouraging his students to discard ‘baneful individuality’,[48] and promoting players ‘ … who have no time to stop and think about themselves … ’ [49]

Along with discipline and teamwork, Langley argued that sport improved courage and physicality. He was one of those men who, Albert Grundlingh argues, saw rugby as a ‘sport of combat’. [50] In 1907 Langley penned an article titled ‘Some Reflections on Sport’ in which he claimed, based on his personal experiences during the campaign, that schoolboy sport in Natal assisted an ‘insignificant number’ of Natal’s young settlers in suppressing ‘hordes of blacks’ during the Bhambatha Rebellion. [51] The parallel between sport and colonial combat was made in many of his speeches:

The qualities developed on the football field […] held good under conditions of life and death […]They [colonial troops] invariably acted as I had often seen them act […] in many a hard fought match, and the spirit of camaraderie bred of sport was always there to help under all conditions …[ 52]

Langley explained that colonials were not born soldiers but developed martial qualities after playing rugby at school:Watch the youngster playing for the first time […] he is conscious of a surging mass of humanity around him, of being borne along in a shockingly helpless state, and he loses the first bit of egoism bred of being the ‘inkosan’ of a three-thousand acre farm. There are really overwhelming forces on this earth from which he must defend himself, and he has to make himself fit to cope with them. If he tries to shirk, he is banged back into the ruck, so he gives up trying to shirk and does his best […] he next learns that he is capable of giving assistance to a hard-pressed partner, but he must be quick, and does it at risk to himself. Rapidity of thought and action are developed … [53]

Team sports such as cricket and rugby also secured class interests. Langley believed that both cricket and rugby required what he called ‘gentlemanly instinct’ [54] as they required gentlemanly qualities such as fair play, teamwork, ‘pluck’ and self-sacrifice. Langley was not alone in his assumption as many of his generation and socioeconomic class, viewed cricket and rugby as a middle to upper class game. [55] Hence the cliché, ‘football is a gentleman’s game played by hooligans and rugby is a hooligan’s game played by gentleman’.When Langley arrived at DHS from MC in 1910 he used cricket and rugby to promote DHS as an upper-class public school. His efforts in this regard are abundantly evident in the pages of the DHS Magazine, his memoirs and The Natal Mercury. In early 1917 a team comprised solely of English public school boys played cricket against DHS. The editor of the June 1917 edition of the school magazine claimed that

in many respects this was a particularly appropriate match, and one possessed of a unique interest, for of recent years – since Mr Langley took control – the High School has been conducted on English Public School lines … [56]

Later that year, Langley organised a rugby match between DHS and a team comprised of public-school-educated Army officers who had been training in South Africa and due to transfer to India. These games highlight Langley’s attempts to get his students to act like and socialise with English public school boys.Langley pursued his agenda by vilifying schools which did not play cricket and rugby, and were, following his logic, lower class. Langley’s rants against ‘the Tech’ (Technical High School which later became Glenwood High School), whose premier winter sport was initially soccer, are legendary: ‘The Tech is the place for swine like you!’ [57] ‘Fight, you swine! Fight, you Technical Soccerite! I won’t have any malingering in my school!’ [58] Towards the end of his career, his policy found vindication in a report of The Natal Mercury of 18 April 1931 which reported that DHS ‘still proudly maintains the traditions of an English Public School.’ [59]

Corporal punishment, privation and prefects

Whilst Langley’s promotion of cricket and rugby received praise from the local press and sporting unions at the time, his use of the cane cemented his legend and is the aspect of his educational philosophy that this still discussed. Corporal punishment, along with an environment of privation and hierarchy, are best referred to as Langley’s covert curriculum as they, together with sport and the classics, encompassed the moral and social lessons which he sought to pass on.[60]

Strict discipline, Spartan living conditions, and pupil hierarchy and privilege systems were common at British public schools in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [61] This tradition was replicated at South Africa’s private and government ‘public schools’ and has only died out recently. The staff and parents [62] of these schools endorsed practices such as corporal punishment, initiation, prefects, fagging and privileges, believing that these practices improved character. [63] One of the main objectives of these practices was an overall process of hardening, a process that could only be achieved by removing boys from the ‘feminine comforts’ of home [64] to produce young men ‘who were tough, realistic, unsqueamish and stoical’. [65]

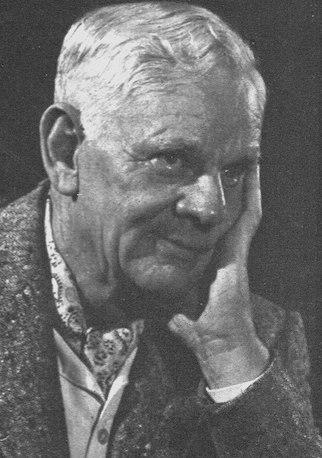

Langley experienced this regime in his own life as a young man both at home and at Kingswood [66] in his later life.[67] He believed it had been the making of him and so implemented the hardening regime with zeal. Tony Voss, in his analysis of Roy Campbell’s literature, refers to Langley as Campbell’s ‘Plagosus Orbilius’ (his ‘flogger’) as he studied under Langley at DHS. Campbell himself called Langley ‘the surly tutor of my youth’ in his autobiography Light on a Dark Horse.

The phrase ‘good measure’ in the earlier smoking anecdote explains how Langley justified frequent beatings. As Robert Morrell surmised, ‘Corporal punishment was not just a manifestation of the power of senior over junior, it was part of a system that socialized boys into gentlemen, creating manliness as it did so’.[68] The toughening aspect of Langley’s use of corporal punishment was not lost on Langley’s students, the majority of whom preferred caning to non-physical punishments. Whilst some of them were undoubtedly humiliated and scarred by the experience, most would proudly bare their ‘cuts’ to their peers. Some boys would even challenge one another to ‘races’ to see who could get the most strokes over a stipulated period of time.[69] David Brokensha, who enrolled at DHS shortly after Langley’s retirement, explains that caning improved a boy’s ‘cred’.[70]

The histories of MC and DHS are full of references to harsh living conditions which complemented Langley’s toughening regime. Men who boarded at these schools as students under Langley describe the conditions as ‘Spartan’, offering little in the way of human and material comfort. Former MC student, Denzil Will recalled how boys were forced to endure cold showers that were exposed to icy winds coming off the Drakensberg. [71] Whilst these conditions were bad enough, the source of most discontent amongst Langley’s boarders was the food and/or lack thereof. Throughout this period, MC and DHS boarders managed to survive on maize porridge and bread. Luxuries such as meat and sugar were rare if not foreign commodities.[72]

Jack Cope, famous author and boarder at Langley’s DHS, told his son that, ‘they [boarders at DHS] were perpetually hungry’ and that DHS ‘always served stale bread first – so that the boys would eat less … ’[73] Apparently the food situation under Langley was so bad that he and his friends ‘smuggled meat out of the boarding house and had someone [Michael Cope recalls that it may have been the District Surgeon] declare it unfit for human consumption, causing a minor scandal.’[74] Whilst we have found no evidence of this scandal, this tale highlights how tough it was schooling under Langley.

Another aspect of Langley’s covert curriculum was pupil hierarchy. During Langley’s tenure older boys were given the responsibility of maintaining the school’s traditions. In his 1913 speech day address Langley congratulated the sixth form for upholding ‘the best traditions of the school’, ‘the steadying influence they had shown’ and their ‘manly lead in all the details of school life.’[75] Along with dress and service privileges, Langley allowed his prefects to cane junior boys. David Brokensha recalls that on his first day at DHS, he was caned by the Head Prefect ‘Skonk’ Nicholson for failing to remove his basher when walking under DHS’s memorial arch.[76]

The public schools’ hierarchical and privilege system was an intentional microcosm of the British Empire and its imperial service and Langley acknowledged this in his farewell message in the June 1931 edition of the DHS magazine when he assessed that ‘pride of school and tradition are in the hearts of all; the leaven is working, and boys will serve their state as they have served their School’.[77]

The Classics

In his memoirs, Langley claimed that when he assumed headmastership of DHS in 1910

modern ideas of education launched themselves full tilt at the established order of things, and the old head [his predecessor, W.H Nicolas …] sorrowfully wagged his head at the probable abandonment of Latin. But Latin came to stay for another twenty years …[ 78]

As the above passage makes evident, classical subjects were essential elements in Langley’s educational philosophy and he defended them against repeated arguments in favour of technical and modern subjects by highlighting their ability to improve one’s social status, character, mental stamina, and imperial spirit.As early as the mid-nineteenth century, British critics stressed the impracticality of learning ancient languages and literature unless you intended on pursuing an academic or legal career. [79] Since most of Natal’s colonists were engaged in agricultural and commercial pursuits in the late nineteenth century, it is not surprising that a similar debate occurred in the Natal. In late 1882, the Governor of Natal, Sir Henry Bulwer, established a commission of enquiry to assess the state of secondary education. Three months later the commission filed a report which claimed that MC and DHS ‘provided a form of education which the majority of the inhabitants considered was not practically useful for the positions in life most of them would occupy’.[80]

Langley’s relationship with classics began with studying Latin, Hebrew and ancient Greek with his father [81] and it continued at Kingswood.[82] Although Langley’s strongest school subject was drawing,[83] his passion for classics saw him successfully complete a Bachelor of Arts Degree via correspondence with the University of the Cape of Good Hope in the late 1890s under the tutelage of MC’s classics-obsessed headmaster, Robert Clark. As a trained classicist, Langley adopted the same arguments as classicists who were trying to maintain their dominance over academia against arguments regarding the subject’s impracticality. He argued that the classics improved one’s social status, cultural appreciation, mental stamina and understanding of empire.

In Britain many argued that a classical education’s lack of practical application greatly enhanced its prestige, as only the wealthy could afford to engage in studies that did not have practical benefits.[84] Using this logic, many middle-class families might have felt a strong incentive to have their sons schooled in ancient languages as this education ensured that boys would associate and be able to communicate with, and secure a position in, the upper echelons of British social hierarchy.[85]

The ability to dye one’s wool in the colours of the upper classes was not lost upon the Britain’s colonial cousins in Natal, the vast majority of whose ancestors had migrated to the colonies to escape a life of poverty. Many of these colonists, now wealthy landowners who lorded over indigenous peoples, sought to entrench their newfound upper class status by sending their sons to schools modelled on the public schools of England.[86] Langley understood this desire and marketed his school as an institution that would produce the leading elite of the colony.

Langley saw his school as an institution for higher education, and a place where boys prepared for the university entrance examinations, not employment. According to Langley, the educational department of Natal ‘was in the hands of primary (education) men’ who misunderstood the purpose of high schools and ‘the public school ideal’.[87] Langley regarded technical education as primary in nature and only fit for the working-class whites and Africans. Because he saw the boys who he taught as the future governing class of the colony, he believed that technical and monetary aspects of commerce and industry were beneath them.

This elitism and social ambition is evident in an address he delivered in 1913 at DHS. His address, which highlights his only conflict with Natal’s Education Department, claims that the government’s efforts to make education cheap, more accessible and practical had led to a general drop in the level of education. He stressed that South Africa was in dire need of educated leaders and those young men who had received substandard education or who had had their studies prematurely cut were likely to be ‘pitched into store or office […] destined to be nothing more than a subordinate’. Passionately, he informed the audience that ‘all public school boys should be placed in such a position educationally that they can climb if ambition calls’.[88]

Langley’s obsession with the classics and social mobility also saw him extend his invective against ‘the Tech’ which, along with the sins of playing soccer, prided itself on its technical curriculum. The elitist messages that permeated Langley’s arguments in favour of classical curriculum and rants against ‘the Tech’ and its vocational subjects were passed on to the pupils who attended the ‘public schools’ of Natal. Such is evident in the reminiscences of Q.E. Carter, MC class of 1922, who recalls how he and his friends would refer to ‘low class fellows […] not attending College (MC), Hilton, Michaelhouse or DHS as “Borvers”’ [89] (lower class boys).

The classics were also considered elite and worthy of defence because of the morals and high culture contained within the curriculum.[90] British ethics and culture versus utilitarian practicality seem to be at the heart of the debate surrounding the validity of classical subjects and Langley was staunchly anti-utilitarian. In 1909 he said ‘for those who stay comes the Matriculation, which opens the door to […] broader fields of literature of which they had no idea before, and also a capacity for appreciating them’.[91]

In 1913 he said:

[Y]our farmer is not a worse farmer for being a gentleman of literature, your business man is not a worse business man because he possesses that which will keep his nature from shrivelling up into that of an accountant’s clerk, with a horizon bounded by figures and farthings – arrogant in the knowledge that he is an animated multiplication table. The difference between craft and culture must be observed.[92]

This Wordsworthian romantic ideal that rejected the dominance of utilitarian practically seems to have taken root in his students as is clearly evident in the DHS Herald’s editorial of September 1917:we would deprecate that view which looks upon education, upon schools and examinations, as glorified workshops for turning out automatons […] we deplore the effort being made in this our very modern day to substitute for certain subjects in the school and university curricula others ‘that will be of more use to the scholar in after life’ […] may we forever be preserved from a system that would gauge all things by the standard of utility, for if you are going to cut out all the superfluities of life you are going to take away all that makes life most worth living. [93]

This classical spirit is even evident in later writings of one of Langley’s most rebellious students, Roy Campbell. Campbell detested Langley but nevertheless became attracted to ‘an ideology of classicism’ in later life and this resulted in his epic translation of Horace’s Ars Poetica. [94] Grudgingly, Campbell admitted that he owed Langley ‘the best half of my character’.[95]Along with social status and culture, classics were held to encourage self-discipline and a sort of ‘mental stamina’ as the masters teaching Latin and Ancient Greek placed a great deal of emphasis on grammar and syntax. This strategy, known as the ‘gerund grind’ or ‘grammar grind’,[96] was so intense that some students felt that mastery of the classics required ‘parade ground discipline’.[97] Langley’s use of rote memorisation in promotion of ‘mental stamina’ is evident in a story told by Neville Nuttall, a former student and later close teaching colleague of Langley’s. According to Nuttall, in a story told to his son, a young boy raised his hand in Langley’s Latin class one day and asked after the meaning of a Latin phrase they were learning. Langley turned to the boy and said: ‘never mind what it means my boy, you learn it’.[98] In 1909 Langley described the preparation necessary before exams as an arduous hike full of ‘slippery places’ and ‘steep climbs’.[99] Stamina and discipline were key.

The fourth and final benefit Langley and his peers believed a classical education bestowed on students was imperial spirit.[100] These men believed that upper class boys needed a sound knowledge of the histories of the Roman and Greek empires to comprehend classical texts and the realities of their own empire.[101] According to Francis Jones, classical education played a significant role in ensuring that the British Empire would rarely have to conscript her men into military or governance roles [102] because classically trained students perceived the British Empire as majestic, natural and as potentially fragile as its Roman predecessor.[103]

Conclusion

Aubrey Langley is described by one of his former students at MC, Edgar Brookes, in the standard History of Natal as ‘one of the most famous and controversial of Natal’s headmasters’.[104] Peter Randall describes Langley as trying to run DHS as a ‘super-English-public-school’ featuring ‘snobbery, class pride, arrogance and public school mystique’.[105] Langley is remembered over a century after he took over the leadership of DHS not just because of his idiosyncrasies and belief in rugby, the cane and the classics, but also because he was part of a process that cemented the school as a leading contributor to South African elites. In 1974, when Hendrik W. van der Merwe published his study of South African English elites, he discovered that of all South Africa’s English-speaking schools, DHS was the biggest contributor.[106] These were men many of whom would have attended DHS under Langley. And the idea that DHS produced boys who could succeed remains to this day, carried into the sporting domain for example, by the Zulu-speaking cricketer, Lance Klusener and the national cricket team captain, Hashim Amla.[107]

In this paper we have examined aspects of Langley’s DHS career, revealing a flamboyance that brought him to the attention of pupils and parents alike. We show how in his office as headmaster he perpetuated a ‘colonial mentality’ amongst the boys who became influential men. This mentality reflected the elite schooling system of the UK and was inflected with racial anxiety. This combination contributed to a school regime that explicitly sought to produce boyhood masculinities that emphasised toughness, discipline, teamwork and an affiliation to empire that Langley believed would secure the colonial order. If recent educational histories have shown how schools for African and Indians operated as sites of subtle resistance, then our study shows equally how amongst the white ruling class, schools gave shape to a particular gendered and classed order.

Acknowledgements

This work draws extensively on the MA thesis (Department of History), UCT, titled ‘The Classics, the Cane and Rugby: The Life of Aubrey Samuel Langley and his Mission to Make Men in the High Schools of Natal, 1871–1939’ (2016). This analysis would not have been possible without the sage advice and support of Matthew Marwick and Jean Thomassen.

Notes

1 H. Jennings, The DHS Story, 1866–1966 (Durban: Durban High School and Old Boys’ Memorial Trust, 1966), 121.

2 M. Peacock, Some Famous Schools in South Africa. Vol. 1: English Medium Boy’s High Schools (Cape Town: Longman, 1972), 54.

3 Jennings, The DHS Story, 118.

4 Natal Mercury, 24 December 1939.

5 P. Randall, Little England on the Veld: The English Private School System in South Africa (Sandton: Ravan Press, 1982), 67.

6 J. Lambert, ‘South African British? Or Dominion South Africans? The Evolution of an Identity in the 1910s and 1920s’, South African Historical Journal 43 (2000): 197–222.

7 The current gender-neutral term for the head of a school is generally ‘principal’ but we retain the term headmaster to emphasise its gendered nature in the period under discussion.

8 S. Vietzen, A History of Education for European Girls in Natal, 1837–1902 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1980), 305–307.

9 E.H. Brookes and C. de B. Webb, A History of Natal (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1965), 263.

10 G. Vahed and T. Waetjen, Schooling Muslims in Natal: Identity, State and the Orient Islamic Educational Institute (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2015), 31.

11 M. Healy-Clancy, A World of Their Own: A History of South African Women’s Education (Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2013); Vahed and Waetjen, Schooling Muslims.

12 R. Morrell, From Boys to Gentlemen: Settler Masculinity in Colonial Natal 1880–1920 (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2001), 57.

13 K. Rousmaniere, ‘Go to the Principal’s Office: Toward a Social History of the School Principal in North America’, History of Education Quarterly, 47 (2007): 1.

14 T.E. Deal and K.D. Peterson, The Principal’s Role in Shaping School Culture (Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED): Washington DC, 1990).

15 N. Etherington, ‘Jeff Guy’s Theophilus Shepstone: A Study in Character’, Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 90 (2016): 75–76.

16 J. Swain, ‘Masculinities in Education’, in M. Kimmel, J. Hearn and R.W. Connell, eds, Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2005), 213–229.

17 T.J.H. Bishop and R. Wilkinson, Winchester and the Public School Elite: A Statistical Analysis (London: Faber & Faber, 1967); J. Chandos, Boys Together: English Public Schools 1800–1864 (London: Hutchinson, 1984); C. Heward, Making a Man of Him: Parents and their Sons’ Education at an English Public School 1929–50 (London: Routledge, 1988); J. Tosh, ‘What should Historians do with Masculinity? Reflections on Nineteenth-Century Britain’, History Workshop Journal, 38 (1994): 179–202.

18 J.A. Mangan, Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School: The Emergence and Consolidation of an Educational Ideology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

19 Randall, Little England on the Veld.

20 J. Gardener, Bishops 150: A History of the Diocesan College, Rondebosch (Cape Town: Juta, 1997), 12.

21 M. Poland, The Boy in You: A Biography of St Andrew’s College, Grahamstown, 1855–2005 (Simonstown: Fernwood Press, 2008), 148.

22 Poland, The Boy in You, 201.

23 P. Rich, Elixir of Empire: The English Public Schools, Ritualism, Freemasonry, and Imperialism (London: Regency Press, 1989), 37.

24 Maritzburg College Magazine (MCM), June 1908, 9.

25 MCM, July 1916.

26 Natal Carbineers Muster Roll, Natal Carbineers Archive, Pietermaritzburg.

27 A. Koopman, ‘UMahlekehlathini, uMehlomane, and uMbokodo’, Natalia, 44 (2014): 48–69.

28 Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, The Wesleyan Missionary Notices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1861), 16.

29 A. Langley, Youthful Reminiscences of Natal in the Seventies (unpublished), 1. Jean Thomassen's Family Records, Durban.

30 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences of Natal in the Seventies, 9.

31 Kingswood School Magazine, December 1936, 47.

32 S. Haw and R, Frame, For Hearth and Home: The Story of Maritzburg College 1863–1988 (Pietermaritzburg: MC Publications, 1988), 165.

33 J. Stalker, The Natal Carbineers: The History of the Regiment from its Foundation, 15th January 1855 to 30th June 1911 (Pietermaritzburg: P. Davis & Son, 1912).

34 N. Watson, S. Weir and S. Friend, ‘The Development of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain and Beyond’, Journal of Religion and Society, 7 (2005): 1–21.

35 B. Haley, The Healthy Body and Victorian Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978).

36 J. Philips and J Nauright, ‘The Hard Man: Rugby and the Formation of Male Identity in New Zealand’, in J. Nauright and T.J.L Chandler, eds, Making Men: Rugby and Masculine Identity (Ilford: Frank Cass, 1996), 84.

37 Great Britain, ‘Inter-Departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration’, Report on Physical Deterioration (1904), 83.

38 S. Hynes, Edwardian Turn of Mind (New York: Random House, 2011), 22.

39 J. Nauright, ‘Colonial Manhood and Imperial Race Virility’, in Nauright and Chandler, Making Men, 122.

40 MCM, June 1908, 19.

41 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 11.

42 MCM, June 1907, 41.

43 MCM, September 1903, 27.

44 A. Herbert, The Natal Rugby Story (Durban: Shuter & Shooter, 1980), 76–81.

45 In stark contrast, Langley’s only son Noel, who did not attend his father’s funeral, served as the masculine antithesis of these men. Noel did his best to avoid the team sports offered at DHS which he regarded as ‘meaningless and a waste of time’. Noel’s athletic apathy served to sever any feeling of warmth between Langley and his son. Langley regarded Noel as a ‘betrayal of fate’ and ‘born to discredit him’. Noel loathed his father and considered his death in 1939 a personal victory.

46 MCM, June 1908, 18–19.

47 MCM, October 1905, 31.

48 MCM, October 1905, 30.

49 MCM, December 1907, 31.

50 A. Grundlingh, A. Odendaal and B. Spies, Beyond the Tryline: Rugby and South African Society (Johannesburg: Ravan, 1995), 113.

51 MCM, June 1907, 19–21.

52 R. Morrell, From Boys to Gentlemen, 111–112.

53 MCM, June 1908, 19–20.

54 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 27.

55 A. Paton. Towards the Mountain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 114.

56 DHS Magazine, June 1917, 18.

57 Jennings, The DHS Story, 126.

58 R. Campbell, Light on a Dark Horse: An Autobiography, 1901–1935 (London: Hollis & Carter, 1969), 73.

59 The Natal Mercury, 18 April 1931.

60 S. Gamaliel and V. Mkuchu, Gender Roles in Textbooks as a Function of Hidden Curriculum in Tanzania Primary Schools (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2009).

61 F. Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii: Public School Education in the Victorian Era, the Classical Curriculum, and the British Imperial Ethos’ (Honours thesis, Wesleyan University, Middletown, 2008), 14.

62 J. de Honey, ‘Tom Brown’s Universe: The Nature and Limits of the Victorian Public Schools Community’ in B. Simon and I. Bradley, eds, The Victorian Public School: Studies in the Development of an Educational Institution (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1975), 22.

63 R. Morrell, ‘“Synonymous with Gentlemen”? White Farmers, White Schools and Labour Relations on the farms of the Natal Midlands, c1880–1920’ in J. Crush and A.H. Jeeves, eds, White Farms, Black Workers: The State and Agrarian Change in Southern Africa, 1910–1950 (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1997), 174.

64 F. Neddam, ‘Constructing Masculinities under Thomas Arnold of Rugby (1828–1842): Gender, Educational Policy and School Life in an Early-Victorian Public School’, Gender and Education, 16, 3 (2004), 305.

65 J. Tosh, ‘“A Fresh Access of Dignity”: Masculinity and Imperial Commitment in Britain, 1815–1914’ In History and African Studies Seminar (Seminar, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 1999), 15.

66 Kingswood School Magazine, December 1936, 47.

67 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 8.

68 Morrell, ‘Synonymous with Gentlemen’, 178.

69 R. Morrell, Masculinity and the White Boys’ Boarding Schools of Natal, 1880–1930’, Perspectives in Education, 15, 1 (1994), 15.

70 D. Brokensha, ‘Youth’, Brokie’s Way: An Anthropologist’s Story, www.brokiesway.co.za/youth.htm, accessed 16 December 2015.

71 Haw and Frame, For Hearth and Home, 229.

72 Morrell, ‘Masculinity and the White Boys’, 19–20.

73 Correspondence with Michael Cope, 15 March 2014.

74 Ibid.

75 DHS Magazine, March 1914, 4.

76 Brokensha, ‘Youth’.

77 DHS Magazine, June 1931, 2.

78 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 23.

79 Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii’, 4–5.

80 Jennings, The DHS Story, 51.

81 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 9.

82 Register of Kingswood School, 1748–1922 (1923), 107.

83 The Kingswood Magazine, September 1885, 21; August 1887, 14.

84 Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii’, 4–5.

85 Ibid., 32–33.

86 Morrell, ‘Masculinity and the White Boys’, 6–8.

87 Langley, Youthful Reminiscences, 25.

88 DHS Magazine, March 1914, 4.

89 Q.E. Carter, The Book of College according to QE. (Unpublished). Maritzburg College Archives, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

90 Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii’, 21.

91 MCM, December 1909.

92 DHS Magazine, March 1914, 4–5.

93 DHS Magazine, September 1917, 2.

94 Tony Voss, ‘Where Roy Campbell Stands’, Literator, 34, 1 (2013): 6.

95 Campbell, Light on a Dark Horse, 71.

96 Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii’, 36.

97 R. Ollard, An English Education: A Perspective of Eton (London: Collins, 1982).

98 Conversation with Michael Nuttall (2 February 2015).

99 MCM, December 1909, 7.

100 Jones, ‘Tirocinium Imperii’, 1.

101 Ibid., 48–49.

102 Ibid., 65.

103 Ibid., 122–123.

104 E.H. Brookes and C.de B. Webb, A History of Natal (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1965), 253.

105 Randall, Little England on the Veld, 5.

106 Ibid., 10–11, citing H.W. van der Merwe, M.J. Ashley, N.C.J. Charton and B.J. Huber, White South African Elites: A Study of Incumbents of Top Positions in the Republic of South Africa (Cape Town: Juta, 1974).

107 B. Carton and J. Nauright, ‘“Last Zulu Warrior Standing”: Cultural Legacies of Racial Stereotyping and Embodied Ethno-Branding in South Africa’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 32, 7 (2015), 876–898.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)