|

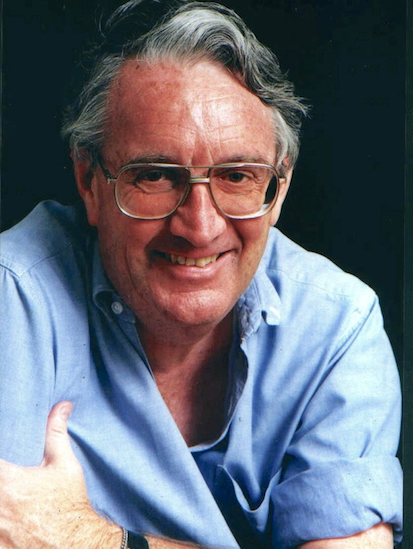

Tim Couzens started out with the Class of 1960 but joined us in 5th form. As he explained on our website, "I was kept back in standard nine, perhaps because I was very small and very young....At the time I resented being held back deeply. But, in hindsight, I think the decision was brilliant (I do not know who I have to thank for it, but there must have been far-sighted teachers among them)". Tim became a member of 5AMA and then 6AMA, the first two Advanced Math forms at the school. He was a cheerful and witty schoolmate, and also an intellectually gifted one: he matriculated with distinctions in four subjects (History, Maths, English, and Physical Science). Tim was also an enthusiastic hockey player and cricketer, and at one point captained the Colts team.

After leaving DHS, Tim attended Rhodes University where he took a B.A.Hons in 1965; Oxford University where he took a B.A. in 1968 and an M.A. in1973; and the University of the Witwatersrand where he was awarded a Ph.D in 1980.

Tim entered an academic career as a lecturer in English at Witwatersrand University in 1969, and held the post until 1977. During this time he developed a keen interest in African literature and in 1977 he joined the Wits African Studies Institute as a Research Officer, becoming a Professor of the Institute in 1982. He held this post until his retirement. At various times he held other appointments at Wits, including Acting Director of the African Studies Institute, Professor of Literary History at the Institute of Advanced Social Research, Visiting Professor at the Graduate School for Humanities and Social Sciences, and Visiting Professor at the School of Arts. Tim also held visiting appointments at the University of London in 1980, Yale University in 1984, and the University of Cape Town in 1989.

Tim also became a prolific and critically acclaimed author, specializing in literary, military, and cultural history. He wrote hundreds of articles, edited fourteen books, and wrote several books of his own. Among them were:

The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of H.I.E. Dhlomo, 1985. In this book Tim rescued from obscurity the life and works of a pioneering African playwright. He subsequently edited and published works of Dhlomo which might otherwise have been lost.

Tramp Royal: The True Story of Trader Horn, 1992. In this biographical work, Tim researched the history of a famous, world-traveller hobo of the early 20th century. At that time many disbelieved Horn's colourful stories but Tim was able to pick up the fading trail and confirm details of his life and add new historical and cultural context to his wanderings.

Murder at Morija, 2003. In this remarkable, meticulously researched book, Tim presented evidence to solve the mystery of an arsenic murder in Lesotho in 1920. Tim enjoyed crime novels himself and this book, though non fiction, has many of the characteristics of the genre -- suspense, false leads, exhilerating discoveries at new clues.

South African Battles, 2013, is a fascinating description of 36 battles, some well known but many of them obscure, fought over five centuries. One critic described the book as "Sometimes riotous, sometimes tragic, always brilliant."

The Great Silence: From Mushroom Valley to Delville Wood, South African Forces in World War One, 2014. In this history Tim explored the largely forgotten role of South African forces in South West Africa, East Africa, Egypt, and the trenches of the Western Front.

In addition he was co-author of several more books:

Mandela: The Authorized Portrait, 2006, a biography that included Tim's own interview with Mandela. (Tim brought along three recording devices for the interview, just in case there was any malfunction!) The book has sold almost half a million copies.

A Simple Freedom: The Strong Mind of Robben Island Prisoner No 468/64, 2008. The book weaves together Kathadra's poignant reflections on three decades imprisonment with poetry, proverbs, and passages from literature and philosophy.

Nelson Mandela: Conversations with Myself, 2010. Tim conceived the style of this compilation of Mandela's writings after the meditations by the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The book has been translated into over two dozen languages.

Tim also was also a highly regarded travel writer, and eventually published a collection of his articles in Rediscovering South Africa: A Wayward Guide (2001). He served on various editorial boards, where he encouraged other writers. He received several awards for his own writing, such as the CNA Literary Award (1992), the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award (1993), and the TravelTour Media Award, 1993.

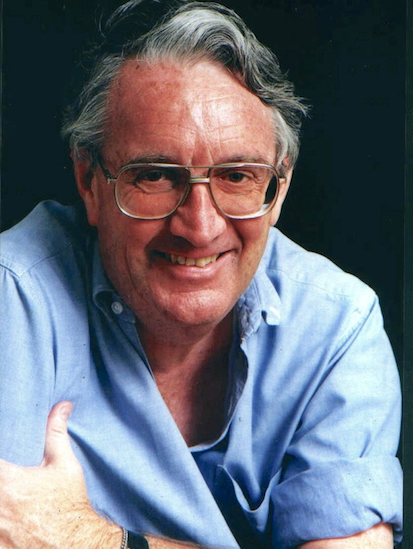

Tim attended our 50th Anniversary celebrations in Durban in 2011, where we found that the elfin boy of our memory had turned into a tall, burly, and imposing man of letters! He also attended a Johannesburg gathering organized by Peter Elstob in October 2014 -- see photo below, with Tim at left accompanied by Nick Gray, Peter Elstob, Ron Wellisch, John Barlett, and Bruce Sparks:

.jpg)

When we started to organize our 55 Year Reunion Lunch in Johannesburg in July, we learned that Tim had recently suffered a stroke. Fortunately he was well enough to attend, and he was in convivial mood, with his only complaint about his condition being that he was not as energetic about his writing as before:

(1).JPG)

In mid-October 2016 Tim got up in the middle of the night, but unfortunately lost his balance and fell backwards, sustaining a severe head injury that caused a haemorrhage on the brain. He fell into a coma which lasted until he passed away on 26 Ooctober.

Tim is survived by his wife, Diana, who had been his partner for 32 years, their two children, and three children by a previous marriage.

|

![]()

.jpg)

(1).JPG)

Ian Robertson

The following obiturary by the South African writer Brian Willan was published in the Mail&Guardian on 4 November 2016:

Tim Couzens (1944-2016)

South Africa has lost one of its great writers and many people have lost a great friend. For over 40 years Tim Couzens entertained and informed, as the author of a stream of books and articles that challenged South Africans to ask who they are, reminded them of their common heritage, and shared his deep knowledge of the historical experience and literature that so fascinated him.

Above all, he was a great storyteller: a master of suspense, of the telling anecdote, the fascinating detail, the pregnant pause.

So seamlessly was all this carried off that it was easy to forget the sheer erudition and the depth of research and reading that always lay behind it.

I first met Tim at a seminar at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in London in 1974. He presented a typically well-researched paper about the connections between an obscure historical episode in 1878 (the Patterson embassy to Lobengula) and its fictional representation in Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines.

In taking this approach, Tim argued, it was possible to see the author’s mind at work, to assess the ideological influences at play in the transition from reality to fiction. You were never going to find the answer in the text alone. It became an article of faith.

Tim at that time was a lecturer in the English department at the University of the Witwatersrand, his first academic job after studying at Rhodes University and then Oxford.

Haggard, however, was not Tim’s real passion. He was already engaged in what would be a long-running and often lonely campaign to recover black South African literature, to fight for its place in the university curriculum, to get benighted colleagues to believe that it even existed.

He wrote about long-neglected black South African writers, championing oral as well as written literary forms and methodologies. It was an uphill struggle.

University English departments were mostly wedded to the Leavisite “great tradition” and were disinclined to look beyond a narrow range of (non-South African) canonical texts. Tim was often frustrated by this adherence to increasingly outmoded views of what literature was all about. Only later would his pioneering efforts come to fruition.

We talk now of “decolonising the curriculum”. The term had not been invented then, but Tim was at it more than 40 years ago. Not only arguing the case but retrieving, in expedition after expedition, research trip after research trip, the materials that made it possible. Without his efforts, much would have been lost for good.

One figure in whom Tim took a particular interest was Solomon T Plaatje, about whom he first wrote in 1971. He was drawn to Plaatje, I can remember him telling me, by his exposure, at Oxford, to writing from other parts of the African continent, particularly authors like Chinua Achebe and James Ngugi.

It inspired him to look closer to home and on to a sustained engagement with Plaatje’s novel Mhudi. His first article, seeking to elucidate its political origins and meaning, was a pioneering intervention that did much to retrieve Plaatje’s reputation as a writer. More followed, along with newly edited and co-edited (with Stephen Gray) editions of the novel itself. Today Mhudi is studied in most South African literature courses, its status assured.

Plaatje was only one of Tim’s many interests. For his PhD he embarked on a study of the writer and playwright HIE Dhlomo, having tracked down and rescued for posterity many of his unpublished writings. A published collection of Dhlomo’s plays followed, co-edited with Nick Visser, along with The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of HIE Dhlomo, now a foundational text for social and literary historians.

From the late 1970s to the late 1990s, Tim found a congenial home in the African Studies Institute at Wits University. Here he was able to pursue his research interests with like-minded colleagues, his work now more in the area of social history than literature. Not that he paid much attention to such distinctions.

What he liked best was getting out and doing what he considered real research — in archives, in old newspapers, in collecting oral histories from elderly informants, black and white, before it was too late.

He was messianic in this mission, travelling the length and breadth of the subcontinent. He had no time for passing intellectual fashions that he thought contributed little to real knowledge and understanding — the Marxist structuralism of the 1970s, for example, or the postmodern and postcolonial theorising of the 1980s and beyond. These were the windmills Tim was always ready to tilt at. An uncompromising inaugural lecture in 1997 (Tim having been appointed to a university chair in literary history) was perhaps the most famous occasion on which he did so.

By this time Tim’s work had reached a far wider audience. His Tramp Royal: The True Story of Trader Horn was awarded the CNA Literary Award and the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award. It told the story of Aloysius Horn, a well-travelled hobo who had ended up in Johannesburg in the 1920s and was taken up by the writer Ethelreda Lewis. Her best-selling book about his exploits, published in 1927, was thought by many to have been largely fiction.

Tim set out to prove otherwise, convinced that it had the air of authenticity. He tracked down, among others, Lewis’s daughter, Trader Horn’s grandchildren — I was with Tim when we knocked on the door of his grandson’s flat on a run-down estate in South London — and he pursued Trader Horn himself across three continents.

Tramp Royal was as much the story of this pursuit as the revelation of the essential truth of Horn’s own tale. Nadine Gordimer thought Tim “combined the talents of an intrepid sleuth with the talents a novelist in the telling of his tale”. Others thought it a vindication of oral history and an extended meditation on the nature of truth in biography.

Tim’s next major book was Murder at Morija (2003). This won no awards but it should have, for this was Tim at his most accomplished. He had come across the story of an unsolved murder of a French missionary, Edouard Jacottet, at Morija, Lesotho, in 1920, and set out to solve the mystery. It nearly killed him too. On a research trip, Tim and several colleagues were caught in the worst snowstorm in a century in the Maluti mountains, and were fortunate to be rescued after eight days by helicopter.

Tim was a great reader of murder mysteries, and a connoisseur of the genre. In Murder at Morija he drew upon this, as well as his love of the Greek classics, combining his well-honed forensic skills with a wider investigation of personal, family and historical circumstances. That in the end there could be no certainty as to Jacottet’s murderer was beside the point. It is a brilliant book, the one he thought his best, ranging as widely as he needed to in order to convey the complexities and layers of meaning of his subject. Just like, he would point out, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a book he rated more highly than any other.

Increasingly, Tim turned to popular rather than academic writing. He delighted in talking about his work to nonacademic audiences, believing he had an obligation to do this, and he found it difficult to refuse an invitation.

After retiring from Wits in 1999 he turned to travel journalism, much of which is collected in Rediscovering South Africa: A Wayward Guide (2001).

Another gem is Battles of South Africa. Far from being a specialist book for military history buffs, it is a wonderfully readable mix of history, biography and travel writing, taking battles — defined rather loosely — as no more than a starting point. Here, as elsewhere, he displayed his instinctive empathy and fascination for people’s lives. Nobody, moreover, was better at conveying a sense of place.

Subsequent projects included playing a crucial conceptual role in Nelson Mandela’s Conversations with Myself (2010), during which he deciphered one of Mandela’s handwritten notes for his Treason Trial speech that had eluded not only other scholars but Mandela himself, and his last book, The Great Silence (2014), an account of South Africa’s involvement in World War I.

Tim’s writings are characterised by an immense generosity of spirit, no surprise to anybody who knew the man himself. He had a special gift for friendship and collegiality. And he had a wicked sense of humour and an irreverence that could leave people perplexed.

He was hugely appreciative of the work of colleagues and disarmingly modest about his own. He had an independence of mind that sometimes led to an uneasy relationship with academia and he had little time for sloppy thinking, or for those whose idea of research consisted of no more than a visit to the library.

South African academic and literary life has lost one of its greatest stars, a true intellectual whose achievements will endure.

Peter Elstob

Orbituary from the Mail & Guardian

ARTS AND CULTURE

OBITUARY: SA owes an intrepid writer, Tim Couzens

Brian Willan

Tim Couzens (1944-2016)

South Africa has lost one of its great writers and many people have lost a great friend. For over 40 years Tim Couzens entertained and informed, as the author of a stream of books and articles that challenged South Africans to ask who they are, reminded them of their common heritage, and shared his deep knowledge of the historical experience and literature that so fascinated him.

Above all, he was a great storyteller: a master of suspense, of the telling anecdote, the fascinating detail, the pregnant pause.

So seamlessly was all this carried off that it was easy to forget the sheer erudition and the depth of research and reading that always lay behind it.

I first met Tim at a seminar at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in London in 1974. He presented a typically well-researched paper about the connections between an obscure historical episode in 1878 (the Patterson embassy to Lobengula) and its fictional representation in Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines.

In taking this approach, Tim argued, it was possible to see the author’s mind at work, to assess the ideological influences at play in the transition from reality to fiction. You were never going to find the answer in the text alone. It became an article of faith.

Tim at that time was a lecturer in the English department at the University of the Witwatersrand, his first academic job after studying at Rhodes University and then Oxford.

Haggard, however, was not Tim’s real passion. He was already engaged in what would be a long-running and often lonely campaign to recover black South African literature, to fight for its place in the university curriculum, to get benighted colleagues to believe that it even existed.

He wrote about long-neglected black South African writers, championing oral as well as written literary forms and methodologies. It was an uphill struggle.

University English departments were mostly wedded to the Leavisite “great tradition” and were disinclined to look beyond a narrow range of (non-South African) canonical texts. Tim was often frustrated by this adherence to increasingly outmoded views of what literature was all about. Only later would his pioneering efforts come to fruition.

We talk now of “decolonising the curriculum”. The term had not been invented then, but Tim was at it more than 40 years ago. Not only arguing the case but retrieving, in expedition after expedition, research trip after research trip, the materials that made it possible. Without his efforts, much would have been lost for good.

One figure in whom Tim took a particular interest was Solomon T Plaatje, about whom he first wrote in 1971. He was drawn to Plaatje, I can remember him telling me, by his exposure, at Oxford, to writing from other parts of the African continent, particularly authors like Chinua Achebe and James Ngugi.

It inspired him to look closer to home and on to a sustained engagement with Plaatje’s novel Mhudi. His first article, seeking to elucidate its political origins and meaning, was a pioneering intervention that did much to retrieve Plaatje’s reputation as a writer. More followed, along with newly edited and co-edited (with Stephen Gray) editions of the novel itself. Today Mhudi is studied in most South African literature courses, its status assured.

Plaatje was only one of Tim’s many interests. For his PhD he embarked on a study of the writer and playwright HIE Dhlomo, having tracked down and rescued for posterity many of his unpublished writings. A published collection of Dhlomo’s plays followed, co-edited with Nick Visser, along with The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of HIE Dhlomo, now a foundational text for social and literary historians.

From the late 1970s to the late 1990s, Tim found a congenial home in the African Studies Institute at Wits University. Here he was able to pursue his research interests with like-minded colleagues, his work now more in the area of social history than literature. Not that he paid much attention to such distinctions.

What he liked best was getting out and doing what he considered real research — in archives, in old newspapers, in collecting oral histories from elderly informants, black and white, before it was too late.

He was messianic in this mission, travelling the length and breadth of the subcontinent. He had no time for passing intellectual fashions that he thought contributed little to real knowledge and understanding — the Marxist structuralism of the 1970s, for example, or the postmodern and postcolonial theorising of the 1980s and beyond. These were the windmills Tim was always ready to tilt at. An uncompromising inaugural lecture in 1997 (Tim having been appointed to a university chair in literary history) was perhaps the most famous occasion on which he did so.

By this time Tim’s work had reached a far wider audience. His Tramp Royal: The True Story of Trader Horn was awarded the CNA Literary Award and the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award. It told the story of Aloysius Horn, a well-travelled hobo who had ended up in Johannesburg in the 1920s and was taken up by the writer Ethelreda Lewis. Her best-selling book about his exploits, published in 1927, was thought by many to have been largely fiction.

Tim set out to prove otherwise, convinced that it had the air of authenticity. He tracked down, among others, Lewis’s daughter, Trader Horn’s grandchildren — I was with Tim when we knocked on the door of his grandson’s flat on a run-down estate in South London — and he pursued Trader Horn himself across three continents.

Tramp Royal was as much the story of this pursuit as the revelation of the essential truth of Horn’s own tale. Nadine Gordimer thought Tim “combined the talents of an intrepid sleuth with the talents a novelist in the telling of his tale”. Others thought it a vindication of oral history and an extended meditation on the nature of truth in biography.

Tim’s next major book was Murder at Morija (2003). This won no awards but it should have, for this was Tim at his most accomplished. He had come across the story of an unsolved murder of a French missionary, Edouard Jacottet, at Morija, Lesotho, in 1920, and set out to solve the mystery. It nearly killed him too. On a research trip, Tim and several colleagues were caught in the worst snowstorm in a century in the Maluti mountains, and were fortunate to be rescued after eight days by helicopter.

Tim was a great reader of murder mysteries, and a connoisseur of the genre. In Murder at Morija he drew upon this, as well as his love of the Greek classics, combining his well-honed forensic skills with a wider investigation of personal, family and historical circumstances. That in the end there could be no certainty as to Jacottet’s murderer was beside the point. It is a brilliant book, the one he thought his best, ranging as widely as he needed to in order to convey the complexities and layers of meaning of his subject. Just like, he would point out, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a book he rated more highly than any other.

Increasingly, Tim turned to popular rather than academic writing. He delighted in talking about his work to nonacademic audiences, believing he had an obligation to do this, and he found it difficult to refuse an invitation.

After retiring from Wits in 1999 he turned to travel journalism, much of which is collected in Rediscovering South Africa: A Wayward Guide (2001).

Another gem is Battles of South Africa. Far from being a specialist book for military history buffs, it is a wonderfully readable mix of history, biography and travel writing, taking battles — defined rather loosely — as no more than a starting point. Here, as elsewhere, he displayed his instinctive empathy and fascination for people’s lives. Nobody, moreover, was better at conveying a sense of place.

Subsequent projects included playing a crucial conceptual role in Nelson Mandela’s Conversations with Myself (2010), during which he deciphered one of Mandela’s handwritten notes for his Treason Trial speech that had eluded not only other scholars but Mandela himself, and his last book, The Great Silence (2014), an account of South Africa’s involvement in World War I.

Tim’s writings are characterised by an immense generosity of spirit, no surprise to anybody who knew the man himself. He had a special gift for friendship and collegiality. And he had a wicked sense of humour and an irreverence that could leave people perplexed.

He was hugely appreciative of the work of colleagues and disarmingly modest about his own. He had an independence of mind that sometimes led to an uneasy relationship with academia and he had little time for sloppy thinking, or for those whose idea of research consisted of no more than a visit to the library.

South African academic and literary life has lost one of its greatest stars, a true intellectual whose achievements will endure.

John Bartlett

It was with deep regret that I learned of the passing of Tim Couzens. I scarcely knew him at school other than that he was a talented cricketer and had won the history prize - which I coverted but was too lazy to work for.This stayed with me and later in life I addressed this by completing a part time degree in History and Economic History at Natal Univerisity, and it was this which eventually broght me in to contact with Tim after our 50th Reunion where we had opportunity to chat.

As we were both Johannesburg based I took the opportunity to get together with him for a breakfast to discuss issues about South African history and politics and to get advice from him as a distinguished author about a novel I am trying to write. This interaction was increased through a get together with some of the other Jo'burg schoolfriends represented in a picture on this site.

I subsequently saw that Tim was a speaker at a major bookfair in Johannesburg and my family and I attended his talk on the role of South African troops in the First World War as it was the 100th anniversary of the war and at which he kept his audience enraptured about the little known activities of our troops in this theatre of war. Tim also mentioned to me at the function that he was launching his book The Great Silence at the SA War Museum which I attended and bought his book in which he inscribed how pleased he was to reconnect - which has been one of the wonderful benefits of this website,

The tributes to Tim through the Mail & Guardian, Sunday Times and the Nelson Mandel Foundation are testimony to the high regard with which Tim was held. The latter organisation mentioned his sense of humour. I was also exposed to this. He mentioned at one of our meetings that there had been a spate of robberies in his neighbourhood. Given the sometimes financial restraints of academic life and given the security issues in Jo'burg, he felt that he should put up a sign outside his home that "this house is protected by poverty!"

I am grateful that I had the opportunity to know Tim, albeit briefly, and will miss his company

John Bartlett

Andrew Layman

Tim and I became firm friends when we were in the same form 9 and 10 classes. Not only did we live close to each other (in Chelmsford Road), but we shared an interest in cricket and were equally amused by some of the comedy of the day. We listened to Peter Sellars' records, among others, until we could recite them word for word. They seemed to be funnier every time we heard them. Then we went to Rhodes together. Tim's brother Roy, who was later the head of Westville Boys, was a warden, I think, in one of the residences. We lost touch a bit at Rhodes. I don't think we were in the same res, and I joined the Rhodes Choir. Between this and other distractions, I failed second year and was brought home to complete my degree. In the meantime, Tim had sailed ahead, of course.

I was very sorry to hear of his untimely death, and feel some shame that it had to be this event that reminded me of the good times we had had together and what a solid friend he had been.

Andrew Layman

Stuart Clark (Class Of 1963)

Having stumbled onto the obituary of Tim Couzens on the Class of 1961 website, I was impressed by the extent of his writings. I was especially intrigued by the subject matter of his book about the service of South African forces in World War 1 - "The Great Silence - From Mushroom Valley to Delville Wood, South African Forces in World War One." In the Introduction to the book Tim bemoans that fact that it is no longer politically correct (my characterization), or of general interest, to study or discuss the gallantry and sacrifice of those South Africans who fought in World War 1. Perhaps not surprisingly. Most of us knew a fair amount about World War 2 because our fathers served in it. But we knew little of the war that our grandfathers fought in. As Tim warns, however, "We must constantly guard against forgetting, constantly be vigilant against the silence."

So I read Tim's book. I am admittedly a bit of a history geek, but I was fascinated by the book, and astonished at the extent of the accomplishments and sacrifices of the World War generation of South Africans. We must indeed be vigilant against the silence. I recommend that you should add Tim's book to your reading lists!

Stuart Clark

DHS Class of 1963

February 6, 2019